In June of 2018, the band then known as Cool American embarked on what at the time felt like a highly experimental West Coast tour routing, the goal of which was to play everywhere conceivably worth playing between Portland and San Diego that I hadn’t already.[1] I met Caitlin on the first day of that tour[2] because she’d booked us an incredible first show in Corvallis, Oregon that set the tone for the whole trip, an (astoundingly) almost totally stress-free two weeks during which our band’s combination mantra and inside joke became “no bad shows”—in retrospect perhaps a nod to the fact that when my bandmates had seen my first draft of the tour routing, they hadn’t figured that would be the case.

I really don’t want to sound like some 19th century ethnographer astounded to find civilization among the bush people—Lord knows there’s enough subtle and even in some cases unintentional condescension tossed around when musicians from bigger scenes talk about smaller ones—so I’ll just say that by that point in my life, I’d played to (sometimes not even) the other bands in the Stocktons and Chicos of the world often enough to know that a good show booked by nice people within spitting distance of I5 between Portland and the Bay area was nothing to scoff at. I’ve been back to Corvallis as often as possible ever since. Thanks to Caitlin and her partner Indiana, who book shows together as Bitter Half Booking, I’ve gotten a bit of a feel for the dedication it takes to foster a vibrant scene in a smaller city where, as Caitlin notes in our chat, many people stick around for just a few years while they attend school.

“Intentional” is the kind of self-help buzzword that gets applied to everything from a meticulously detailed five-year plan to the otherwise chaotic lifestyle of someone who’s finally figured out how to regularly water their houseplant, but I think it really is the best way to describe Caitlin’s approach both to booking and to the music she makes—especially in the hardcore/post punk outfit Flexing. Both strike me as the work of someone who’s pretty familiar with a particular kind of high stakes: the kind where if you don’t set the example, there aren’t necessarily many people around you who’ll pick up the slack.

Flexing is clearly something of a departure from the sound of the other band I’ve seen you play with, Dumb Luck, and I’m curious about what led you in that direction (one y’all pull off very well, by the way). Did you feel compelled first and foremost to make music that was more explicitly political? Or were you drawn initially towards the heavier sound, and the lyrical content followed from there naturally? Do you even make a distinction between the two?

Thank you! Before Dumb Luck I was in a fast punk band called Angries for a long time, so it’s been fun with Flexing to return to a more aggressive style. We started out with the intention of making weird, dark punk—I book a lot of shows, and there weren’t really any aggressive DIY bands in Corvallis at the time, so finding local support for touring hardcore and punk bands had gotten really difficult. Our goal was to fill that gap. Originally we thought we would do more of an angular, post-punk thing, but our songwriting style is pretty freeform and collaborative and the songs we were writing just didn’t turn out that way. Ultimately, I’m glad they didn’t, because it’s given us a lot of space to mine different influences and try different things. That’s something I’ve especially appreciated about playing in this band, that everyone is so willing to experiment and change things over the course of the songwriting process. We don’t have a main songwriter, so someone will bring in an idea and we’ll spend a long time taking it apart and putting it back together until it’s mutated into something totally new.

As for the lyrics, I have always gravitated towards writing about politics, and Flexing started within, like, a month of the 2016 election so it became a way for me to process my feelings about what was happening. There was also a pretty immediate upswing in white supremacist activity in and around Corvallis, so speaking out and claiming space felt even more important. I do think that if we had gone in more of a weirdo post-punk direction that I would have ended up writing more abstract lyrics that were less explicitly political, so yeah, the heaviness and political expression are definitely intertwined for me. There’s a catharsis in it.

I didn’t realize Flexing’s start came so close to that election! I remember how frightening it was to see the far-right undercurrent in Oregon emboldened after that. I think people who haven’t lived in the PNW tend to view it as a very progressive place, at least ostensibly, but as you know, it’s really not that way outside of the cities. And at least in my experience, college towns all over the country can often have a progressive sheen that turns out to be pretty hollow. All the hippy cafes and head shops turn out to be little more than a peeling coat of paint covering up some pretty conservative cultural values held by many of the people who live there—more libertine than liberal, at the very least. To be fair, I haven’t spent enough time in Corvallis to know if that description applies, but I’m curious how you view the place your work (both making music and throwing shows) occupies within your immediate surroundings. It sounds like there’s some element of opposition there, but of course anyone who books as many shows as you becomes something of a local cheerleader. How do you think of it?

I have a love/hate relationship with Corvallis. The DIY scene is great and I’m really proud of some of the stuff we’ve pulled off in such a small town, but it’s definitely not as progressive here as some people would like to believe. People in Corvallis really don’t like being made to feel uncomfortable and are very invested in seeing “both sides” of political issues, which is a problem when one side is literally facism. A few years ago there was this whole thing where a member of the university’s student government was outed as a neo-Nazi, and one of our local papers gave him a front page interview. I guess they were assuming that people would read it and be horrified by his beliefs, which like, sure, but there’s so many ways to write that story that don’t involve essentially handing him a megaphone. The university let him run for re-election on a platform that was basically just the fourteen words (printed in the student paper alongside the other candidates’ platforms) and he got something like 300 votes. It was deeply troubling to watch all these local institutions bend over backwards to accommodate white supremacy like that was the only option. Things that dramatic don’t happen here often, but that situation kind of sums up the basic problem of Corvallis for me—the idea that tolerance is always the ideal we should be striving for, when in reality there are some things that should never be tolerated.

Fostering creative spaces in opposition to that attitude is really important to me, and that’s something I try to do with my bands and the shows I book. To me, shows aren’t just about going to see some bands play, they’re an opportunity to create an alternative environment where marginalized and underrepresented voices are centered and celebrated. That’s why I try to be intentional about the bands I book and one of the reasons I don’t say yes to every single show request. I see myself more as a curator than a promoter.

That’s a great way to put it. The phrase “DIY promoter”—one that gets tossed around quite a bit—has always grated on me a little. It’s not exactly a contradiction in terms, but it’s not a natural fit, either. The line between intentionality and openness can sometimes be difficult to toe when you’re booking a show, in my experience. People in your position who are willing to say no often get accused of “gatekeeping” (another word that frankly I’d be happy to never hear again). Obviously it’s possible to be needlessly exclusionary, but the idea that everyone has a right to everyone else’s time and attention seems totally bizarre. Do you worry much about how to strike that balance?

Yeah, my partner Indiana and I are two of the most visible people throwing shows in Corvallis and we have gotten a lot of flak from local music bros for being too exclusionary. It’s frustrating because we spent several years doing scene-building work—hosting community meetups, tabling at different events, networking with other art and music groups—all with the intention of making the scene as accessible and inclusive as possible. Which, based on the feedback we’ve gotten, I think we did! I’m really proud of how much the scene has grown since 2015 because it took a lot of work. When we’re booking local support, though, we try to keep it limited to bands made up of people who participate in the community. Since the barriers to entry are so low, I feel like that’s not unnecessarily restrictive, and I think that prioritizing community involvement in that way is something that separates DIY from mainstream music scenes. I’ll be the first to admit that personal taste is a big part of how I decide which shows to take on, but I’ve also booked plenty of bands that aren’t as much my thing just because the people are nice and they go to shows sometimes.

Another thing that has caused some friction with the Corvallis music scene at large is the fact that we prioritize punk/indie/”alternative” bands made up of women, people of color, and queer people. Most other people booking shows around town don’t have any sort of set criteria for which bands they decide to do shows for (as far as I know), but most other people are either getting paid to book for a venue or don’t do shows as regularly so it’s easier to say yes to everyone who asks. Before the pandemic, I was getting multiple show requests every week and there’s just no way to do all of it. So no matter what, someone is getting turned down, and my main goal in booking shows is to provide a safe, accessible platform for the creative expression of marginalized voices. That’s not to say I don’t do shows for straight white cis men, because I do and that’s inevitable, but I try to never have them make up the entire bill. I feel like that’s the least I can do as someone who has a say in which bands are given a platform—make an effort to bring in some diversity and to elevate bands that might not get the same attention at a traditional venue.

So to answer your question, I’m not super worried about whether or not someone thinks I’m too gatekeep-y because you can’t please everyone. I’m not the only one throwing shows in Corvallis, so if I say no, the band can go elsewhere and still find an audience. Maybe it would be different if booking shows was my job, but this is all a labor of love for me and I put a considerable amount of effort into every show I book. I don’t think that anyone is entitled to that work just because they want it, especially if they aren’t willing to do the bare minimum and participate in the scene in some way.

It’s interesting to read you contrasting the approach you and Indiana take towards booking with that of people who do it for money, as a paid booker for a bar or whatever. I often feel like people are so accustomed to the transactional nature of pretty much everything in their lives that when they find themselves in a situation that isn’t governed by those rules, they don’t know how to behave. They feel entitled to other people’s time and attention on some level, because in nearly every other arena of contemporary life, they basically are entitled to it—assuming the price is right. They end up bringing this strangely warped version of the mentality that “the customer is always right” to a non-commercial creative space in ways that feel much more gross than they even realize.

Bitter Half’s DoDIY entry seems to address this on some level: in addition to bros and bigots, you list “bands who see DIY as a market to tap into” as a category you’re not willing to book. The underground has obviously had a potent self-mythology of anti-commercialism for a long time, and for just about as long, there have been people trying to use the cultural power of those myths to make money. Do you feel like you can tell the difference when someone hits you up for a show?

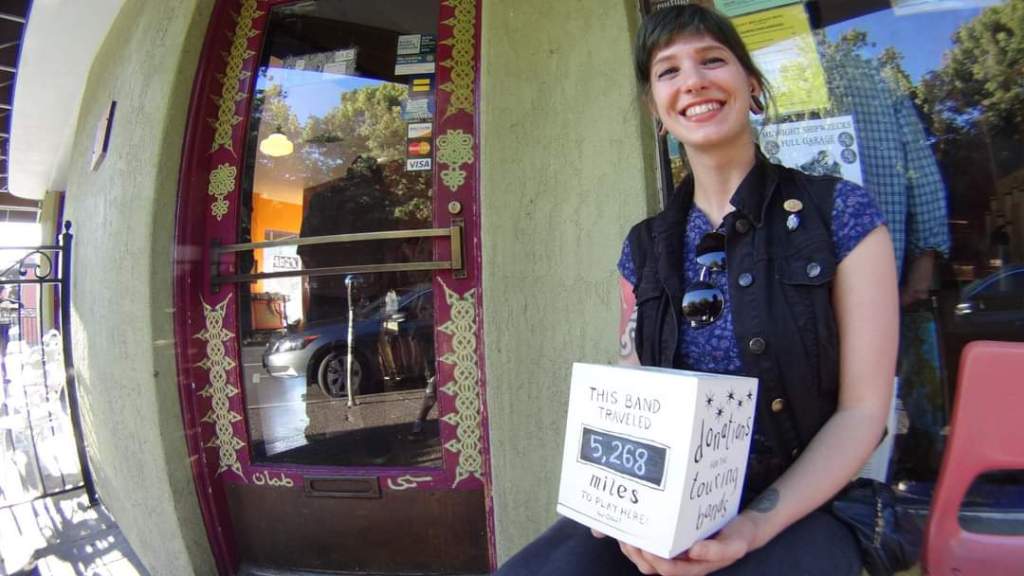

It honestly doesn’t come up that much, but we have gotten emails from bands and agents talking about “the Corvallis market,” which feels a little weird. Those are usually the same people that send EPKs and spammy, form letter-type requests with testimonials and stuff. There’s nothing wrong with being more formal in your show requests, and there’s definitely nothing wrong with sending similar messages to lots of people, but you can usually get a vibe. I don’t think I’ve ever turned anyone down for that reason, though. A lot of the time it comes down to genre—usually the bands working a more professional angle are pretty far removed from the type of music I like to book, so I’ll send them information about other venues and try to hook them up with someone else who would be a better fit. I don’t have a problem with bands trying to hustle and make money, but it’s not my thing and I don’t think that money should be a driving force in a DIY setting. Of course, touring is expensive and I do what I can to encourage as many donations as possible for the touring bands, but in my experience that’s more about making touring sustainable than it is about turning a profit.

It’s always pretty funny to hear booking agent lingo like “market” creep into the vocabulary of bands who play house shows. I have nothing against booking agents; one of the bands I play in has one and it’s been great. But even for people who are totally ensconced in that world, it’s like, you pay the booking agent to talk like that so you don’t have to!

That dichotomy between sustainability and profitability that you mention is a great way to think about the underground. Once you start thinking about sustainability, you realize it involves a lot more than putting money in the gas tank, or even in people’s pockets. It means making the experiences feel valuable in an immaterial sense, which for most music fans is actually a pretty low bar, I think; it also means making them feel rejuvenating and renewing, a much higher bar for people who go to a couple shows a week. That’s one reason I’ve always appreciated the thought and effort you and Indiana put into making the shows you book more than just some bands playing in a room. There’s often a physical artifact of some kind associated with Bitter Half shows—I still have the incredible postcard flyer you made for that Cool American show in February 2019!—or a fun concession or treat. What motivates you to make the experience of show-going a little more holistic?

I love doing goofy shit for shows. One of my favorite projects we did was a punch card for shows over the summers of 2018 and 2019. For every show you went to, you got a punch on the card, and if you got five or more punches then you got a prize at the end of the summer. In 2018 the prize was a hand screened patch and in 2019 it was a mixtape of all the bands that played in Corvallis over the summer (packaged to look like a creamsicle, on a popsicle stick because we are truly extra). Attendance at summer shows in a college town can always be hit or miss, so we hoped that it might encourage people to come out more often. Our goal with stuff like that is to get people invested and to make them feel like they’re an important part of the community, because they are! I think a lot of times simply going to shows is overlooked as the most valuable thing you can do for a local scene. Playing in bands and booking shows is great, but what makes DIY powerful is the community behind it. I like doing crafty stuff and I love a good gimmick, so putting in the extra effort to reward people for their participation is fun for me. I also think that it can make things more accessible, in a way—going to shows where you don’t know anyone can be kind of intimidating, but if someone is handing out friendship bracelets or cookies, it becomes a little more welcoming. Being a college town, Corvallis is very transitional, and people are always coming and going. I want to make it as easy as possible for folks to jump in and get the most out of the DIY scene here before they move away.

Maintaining some positive word of mouth hype is also crucial for a town of our size. We’re constantly fighting against the idea that there’s nothing to do here, and that you have to travel to Portland or Eugene to see any good bands. Getting bands to stop here is also a challenge, because it’s a little town that no one has heard of. We don’t have the luxury of throwing lackluster shows because if a band has a bad or boring experience, they’re never going to come back and they’re going to tell their friends’ bands not to bother stopping here. It’s not like a city where they might give it another shot on their next tour. If we consistently go above and beyond, though, maybe word will get around that there actually is cool stuff going on and we can get more people in attendance and more bands coming through. So while it’s mostly just about having fun and providing a service to the community, there’s also an element of self-preservation to it.

I think word is surely getting around! I feel like most of my friends’ bands on the West Coast know Corvallis is the spot these days, and you certainly seemed to be keeping busy before COVID. Though the pandemic sucked in basically every other way, has it at least felt like a welcome break in that sense? Or are you nervous about being able to pick back up where you left off?

A little bit of both! Before the pandemic I had been saying for months that I wanted to take a break from doing shows, so being forced to take some time off wasn’t a bad thing. Flexing started practicing again recently and it’s been cool to have so much time just to focus on writing. I am nervous about what Corvallis is going to look like after the pandemic, though—we’ve lost three venues so far, and I have no idea what local bands will even exist after this is over. We were already having trouble finding local support for shows and there are several bands I used to book regularly that are defunct or have moved away. But I’m excited to start working on things again, and I think I want to revive some of the community-building activities we did a few years ago. We did a band lottery annually for several years, Band in a Hat, and I’m hoping that we can maybe inspire new people to start bands if we brought that back. I also want to start doing community meetups again. I made a bunch of new friends when we first started doing those in 2015 and I think people are really going to be looking for ways to connect when we’re finally allowed to have gatherings. So I’m nervous but I’m also looking forward to the future.

[1]In addition to a few Oregon shows in towns new to us and a stop in “the biggest little Cool American’s favorite city” Reno—decidedly not new to us—I think we played 8 shows in California. Not exactly Hard Girls 2017 tour, but it still felt like a bold move for our tiny band.

[2]I’d actually played a show with her band Dumb Luck a couple years prior, but embarrassingly, I didn’t really remember much about that night or if I’d actually met her then. It’s total jaded lifer bullshit to say “it all blends together” but I think I’m not alone in that regard, excepting those of us with photographic memories or quick Instagram-follow-button trigger fingers.